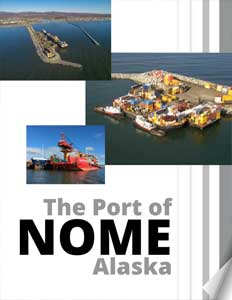

The Port of Nome

Alaska On the Forefront of America’s Arctic

Business View Magazine profiles The Port of Nome, a maritime port, located in Norton Sound on the west coast of Alaska.

The city of Nome, Alaska is located on the southern Seward Peninsula coast on Norton Sound of the Bering Sea. The Port of Nome, the most northern port in the state, has served as a critical transshipment hub for western Alaska and the Arctic for more than a century. Groceries, construction supplies, lumber, gravel, fuel, and other goods flow through the Port before being distributed to some 60 Alaskan communities, spread over 1,000 miles. The existing port and small boat harbor facilities have multiple docks, with a maximum depth of 22.5 feet, and the current marine infrastructure serves a fleet of tug and barge, landing craft, and tanker traffic, as well as government, research, cruise, recreation, and commercial fishing vessels and a fleet of gold dredges.

The Port of Nome has grown considerably over time – from 32 vessels back in 1990, to 160 vessels in 2000, to 635, in 2015. It currently handles an average of 53,000 tons of rock, sand, and gravel; 34,000 tons of freight; and 13.1 million gallons of refined products, annually. It also supports many local seafood harvesters and processors. This past summer, illustrating a growing interest in Arctic cruising, the 820-foot Crystal Serenity, carrying 1,700 passengers and crew, made a port call in Nome on its way to New York City through the Northwest Passage – the largest cruise ship ever to ply that route. “Our activity is building; our traffic numbers are up; our budgets are double what they used to be,” says Port Director, Joy Baker. “I managed the Port by myself for almost fifteen years, and now there’s a staff of five, with frequent support from our Public Works crew for handling large ships, fuel transfers, increased port security, and port services.”

The Port of Nome’s physical structure has been redeveloped several times over the years, with a major project having been completed in 2006 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Today, the Port of Nome is awaiting news on yet another Corps project which, if implemented, will expand to become a deep-draft port with an existing outer harbor that is dredged to 28 feet from its current 22.5. The plan also calls for demolishing a small breakwater at the end of the existing causeway and extending the causeway 2,150 feet. A 450 to 650-foot large vessel dock would then be constructed at the end of the causeway in the newly protected basin to be dredged to 35 feet. The large eastern breakwater would remain in place and the extended causeway would wrap around the end of it to expand the harbor. “We’d be able to accommodate not only the existing fleet that make port calls in Nome,” says Baker, “but we’d also be able to accommodate national security cutters, the existing icebreaker and future models, as well as the foreign-flagged vessels, most of which are too deep to dock, like large cruise ships, oil tankers, research vessels and offshore supply platforms/deck barges.”

Unfortunately, as is often the case in major projects such as this one, there are many bureaucratic hurdles which still have to be overcome. “A draft feasibility study conducting by the Army Corps evaluated 13 sites along the Arctic coast for the ability to develop an Arctic deep-draft port to support the nation, and three locations rose to the top,” Baker recounts. “Those three were further evaluated and Nome was determined as having the greatest potential for initial Arctic port investment based on our existing infrastructure, both onshore and offshore.

But, last year, the situation on the ground changed when Shell Oil pulled the plug on its Arctic-focused explorations and the Corps decided to re-evaluate its decision. “When Shell suspended its operations, they said we’re going to have to rethink this, because under the program we were using, it had to fit into a national economic framework, which does not capture the challenges in Northwest Alaska and the Arctic,” Baker says. But Port Director, Baker, also firmly believes that the Corps erred in its initial analysis by focusing too heavily on Nome’s relationship with the oil and gas industry while neglecting to place enough emphasis on such factors as national security, resource protection, and the Port’s role in staging critically needed search and rescue, as well as oil spill response assets for the Bering Sea.

In any case, the Corps found itself going back to Congress, to get additional language placed in the $10.6 billion Water Resources Redevelopment Act, the underlying legislation for any federally-sanctioned port improvements. That revised bill was passed in different forms in both the House and Senate this year, and Baker says that committee staffs are currently working to reconcile them. During its Lame Duck session, when Congress reconvenes to complete its business before the end of the year, it could potentially approve the compromise bill written by the conference committee, which would then go to the President for his signature.

“Once that happens, it goes to the Corps and they are given their direction, within the new language, on moving forward with the completion of the study and design of an Arctic deep-draft port,” Baker continues. “The intention is for the city to become the non-federal, cost-share sponsor on the study and design completion. We will sign a formal agreement, like we did twelve years ago when we partnered with the Corps to re-locate our entrance channel and build the east breakwater, and proceed to work closely with them on the re-scoping of the study for a final Chief’s Report authorization to move into design. And then, once the design was completed, it would go into another phase to obtain funding for construction.

“It could take maybe a year to re-scope the study and get the Chief’s Report signed, and then likely two years would be the shortest and most optimistic timeline for completing the design, followed by another year or two to obtain construction funding,” Baker adds. “The initial concept, based on results of the first study draft with Nome at the top of the pile, was $212 million, which could increase by the time we reach the construction phase, based on final design features. We’re a small community in a very remote area so the federal government is going to have to play a large role in the expansion of the port facility, based on the ultimate function it will serve to support the military’s Arctic maritime fleets, life safety and environmental protection response assets, as well as our country’s national security.

“If the stars align in Washington to support the development of an Arctic deep-draft port, I’d say it’s realistic that we could break ground in five years. Construction could probably be completed in two ice-free seasons, possibly three, if weather became a factor. It would depend on how much our ice-free periods continue to expand over the next five years. Our shoulder seasons are getting longer now. Fifteen years ago we would not see open water until mid-June and it would start freezing in November. We had open water offshore by May 1st this year, and that area we didn’t start freezing last year until December, with the ice not fully forming until January/February, essentially moving all winter and making it unsafe for ice fishing or traveling with snow machines or track rigs. Things are changing, for sure.”

Baker believes that it’s important that the work begin in Nome as soon as possible for several reasons. One is that the coastline needs to be protected in the event of a major disaster and Nome can provide support for the maritime assets within range for any necessary search and rescue efforts. “Right now, we’re relying on who happens to be out on the water and need to reach out to Russia and Canada to help us respond on larger incidents,” she avers. Regarding Russia, Baker says that while President Putin is busy establishing Arctic seaports and building icebreakers in expectation of continued global warming, which will open up the region further to ocean-going vessels, the U.S. is still trying to evaluate what may or may not be happening in the Arctic and whether it warrants substantial funding and call to action.

“Our delegation is doing a wonderful job in getting more and more of their fellow members to understand that there’s a very large purpose and need for development here. It’s not just what’s going to benefit the community or the region. It’s the fact that Russia is stepping up their operations; it’s the protection of the country, the country’s resources, mariner’s lives, the culture, and our Arctic coastline,” she asserts. “But everything’s on the table, right now, until we get specific direction from the Corps on the re-scoping of the study. Everyone understands what needs to happen here, and we can only hope that everybody stays on the same road and understands how far behind we are.”

Baker says that if none of the hoped-for progress occurs, the Port of Nome will simply “keep functioning as we function now, and continue to drive the discussion on achieving the project goal.” Meanwhile, she, and the rest of Nome’s 3,820 inhabitants, are all watching and waiting. “A great deal depends on what’s happening in the Arctic when Congress is looking at the document,” she says, finally. “There’s a lot of talk about what Russia is doing. Putin is developing a variety of deepwater ports; he’s moving forward. He’s not just sitting and thinking about it like the U.S. He’s expanding his fleet considerably and, I think, everything he does will eventually trigger a reaction to what ultimately comes of this large Corps project.”

Check out this handpicked feature on The Kaskaskia Regional Port District – Moving up and shipping out.

AT A GLANCE

WHO: The Port of Nome, Alaska

WHAT: A maritime port

WHERE: Norton Sound on the west coast of Alaska

WEBSITE: www.nomealaska.org/department/

PREFERRED VENDORS

DIG DIGITAL?