The Tulsa Port of Catoosa

Where the Barges Are Running

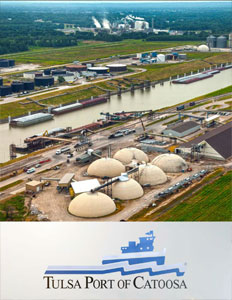

Business View Magazine profiles The Tulsa Port of Catoosa, a major port on the McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System, in Rogers County, Oklahoma.

When Bob Portiss, Port Director of the Tulsa Port of Catoosa, says that “Oklahoma is a maritime state,” eyebrows get raised. “There’s no such thing as a navigable waterway into the heartland of America – none,” someone once sniffed to Portiss after he was advised that Tulsa, indeed, is home to an inland, international seaport. But it’s true. And Portiss, who joined the Port staff in March of 1973, and was appointed to his current position in 1984, tells the story of how the Port came to be, and how it opened up the northeast section of the Sooner State to the wider world of international shipping.

“In the ‘30s, Oklahoma was known as the dust bowl,” he begins. “And it wasn’t just Oklahoma, it was this entire area. We suffered an incredible drought at the same time the nation was going through the worst depression it had ever experienced. Then we came out of the dust bowl in the early ‘40s, and nature decided she’d reverse the trend and gave us so much water that we had some horrendous flooding – not only in our own state, but in Arkansas and Kansas.”

“There were two leading members of Congress,” Portiss continues, “one from Oklahoma – Bob Kerr the founder of Kerr Oil Company, also former governor and U.S. Senator, and one from Arkansas – John McClellan, Senator and Chair of the Appropriations Committee. Together, they agreed that they needed to do something to try and harness Mother Nature or at least tame her down, if they could. Having seen the dust bowl, and having now experienced the flooding, they approached their colleagues in Congress and said, ‘We have to develop a flood control project in these states.’ The cost was half a billion dollars. Congress replied: ‘We’re on the brink of World War II; we can’t afford to spend that kind of money.’”

“They went back to the drawing board, which was indicative of Kerr’s attitude and the way Kerr lived his life,” says Portiss. “He wasn’t about to give up. He went back and determined a way, together with John McClellan: ‘You know, we can make this flood control project into a different kind of project providing not only flood control benefits, but also things like commercial navigation, wildlife conservation, municipal water, hydro-electric power – benefits of that sort.’ And when they returned to the Congress, it said, ‘Okay.’”

So, in 1946, Congress passed the Rivers and Harbors Act, authorizing the construction of a multi-purpose waterway originating at the Tulsa Port of Catoosa and running southeast through Oklahoma and Arkansas to the Mississippi, utilizing three rivers: the White, the Arkansas, and the Verdigris. Construction of the McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System began in 1950. To allow for navigation, in 1963, the Army Corps of Engineers began implementing a system of channels, locks, and dams, in order to compensate for a drop of 420 feet between Tulsa and the Mississippi River, as well as to connect the many reservoirs along the length of the Arkansas River. The first section, running to Little Rock, opened in January, 1969.

In 1970, following Congress’ mandate that several principal cities along the waterway would be required to build ports, Tulsa embarked on the creation of a multi-modal shipping complex and a 2,000-acre industrial park at the head of the waterway’s 445-mile navigation route. The first barge to reach the Port of Catoosa arrived in early 1971, and today, the Port is one of the largest, most inland river ports in the United States. It hosts a diverse list of 70 companies that employ over 3,000 people. In an average year, some 13 million tons of cargo is transported on the McClellan-Kerr by barge; 2.7 million tons move in and out of Catoosa, alone. Numerous industries, including fertilizer companies and industrial gas suppliers utilize water transport to ship bulk freight ranging from sand and rock, to fertilizer, wheat, raw steel, refined petroleum products, and sophisticated, petrochemical processing equipment.

“Our country has 25,000 miles of inland waterway,” says Portiss. “And, as a consequence, our waterway highway enables us to move product from here to Minneapolis/St. Paul; Chicago; up the Ohio River as far as Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; up to Sioux City Iowa; and, of course, down to the Gulf and over to Brownsville, Texas and/or around the coast of Florida, following the Intracoastal Waterway up to Pennsylvania, where we ship a lot of project-related cargo. And of course you have the import/export market. We’re sitting in the grain belt of the U.S., so a tremendous amount of our grain is going to go for export. New Orleans is a spring-wheat market. With the opening of the waterway, we gave our farmers and our elevators an opportunity – a low-cost means, if you will – to reach the spring-wheat market of New Orleans.”

While the Port is a public entity, overseen by a nine-member board, it is run like a business. “We are under a mandate, and have been since the day we opened, to operate in a financially solvent manner,” says Portiss. “We are not tax-supported. We receive no state appropriations; we receive no local tax money. In order to spend a buck, we have to earn a buck.” According to David Yarbrough, the Port’s Deputy Director, approximately 70 percent of those bucks come from the rents that the Port’s tenants pay to operate their businesses on the site. “Besides our lease income, we have operational income that comes from operating our two fleet-switching towboats, and our rail infrastructure, including three switch locomotives,” he adds. “And then, we get just a little bit from tollage and wharfage on every ton of cargo shipped through our Port.”

While shipping is a competitive enterprise, and in some respects, all the ports along the waterway compete with rail and truck transport, Yarbrough stresses that, for some customers, water transportation is the only solution. “If it was not for the waterway, farmers in southeast Kansas would not be able to get their goods to market and be competitive in a global market,” he maintains. “And when it comes to low-margin commodities – Arkansas, for instance, has a pretty substantial sand and gravel business. The margins are so slim on those types of commodities that without the waterway, they’re out of business; they can’t afford to subsist in an environment where all they have is truck or rail.”

In its ongoing pursuit to better serve its tenants and their customers, Yarbrough says that the Port has recently completed a $13 million dock renovation project. “We applied for and were a recipient of a TIGER (Transportation Infrastructure Generating Economic Recovery) grant,” he explains. “It’s a program that came about right after the current administration took office, whereby they funnel funds for infrastructure projects, nationwide. We competed for, and were awarded a $6.425 million grant. We matched that and exceeded it with our own capital. We renovated our 45 year-old dock – all new concrete, new fenders on the face of it; we took down our original, two-hundred ton, overhead bridge crane and replaced all the components; laid 6,000-plus linear feet of new railroad track on our dock to make us better at transloading from rail to truck and truck to rail, as well as rail to barge. It makes us more competitive in the one market that we have an edge in over any, which is the oversize, over-dimensional market. We have the only roll-on/roll-off facility on the river system. If it’s too big to pick up with the crane, you can take it to our roll-on/roll-off wharf where we’ve had loads in excess of 600 tons go through onto barge. We have another project that we’re in the early stages of: to build 1,200 linear feet of additional channel for barge parking, so that we can better utilize our terminal area and our waterfront facilities.”

Looking toward the future, Yarbrough believes that the next opportunity for the Port will be found in handling the big shipping containers that now constitute the bulk of oceanic traffic. “I think we’re headed for a perfect storm of opportunity with the completion of the Panama Canal and with the gridlock on the coastal ports. I think that the Gulf region is going to be more competitive with Asian ships and the container market,” he asserts. “We believe that the inland system, as a whole, can capture that container market. I think that over the next year or two, we’ll have pilot projects to begin moving containers on our system from Tulsa to points globally.”

Portiss agrees. “Another reason we believe that containers will soon move on a regular basis by barge: if you look at the west coast ports, they’re saturated. They’ve not been able to expand. They’ve done a great job handling what they do handle, but with the doubling of international trade, something has to give. Secondly, when you look at the major cities of our country, the congestion in those cities is absolutely incredible. Whereas, in this part of the world, we are open year-round to navigation; all of our modes of transportation are available year-round. We have ample land that’s available for development. There’s no reason in the world that this particular part of our country cannot be – and it will be – a major distribution center. Goods moving up the waterway, moving in here by rail, by truck, and for further dispersion out into the central part of the U.S. There’s no doubt about it.”

Yarbrough seconds Portiss’ positive attitude: “We are not going to wait for somebody to solve this,” he states. “We are going to solve it. We won’t do it alone; we have great partners in companies that own and push the barges. We’re developing relationships with the folks that are in the business of unloading those containers at our coastal ports. We’re going to find a solution that makes sense.”

So, the next time someone doubts that Oklahoma is, in fact, a maritime state; all they need do is check out the Tulsa Port of Catoosa, where the waters are flowing and the barges are running.

Check out this handpicked feature on The Port of Anchorage.

AT A GLANCE

WHO: The Tulsa Port of Catoosa

WHAT: A major port on the McClellan–Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System

WHERE: Near the City of Catoosa, Rogers County, Oklahoma

WEBSITE: www.tulsaport.com

PREFERRED VENDORS

Oklahoma Central Credit Union – The Oklahoma Central Credit Union has helped Oklahomans meet their financial goals, solve problems, and turn opportunities into accomplishments since 1941, by offering them affordable loan rates and a wide range of loan products, including: automobile, home, and student loans. It currently has 40,856 members and assets of over half a billion dollars. – www.oklahomacentral.org

Kelvion Inc. – As a successor to the GEA Heat Exchangers Group, Kelvion offers its customers one of the world’s largest portfolios in the field of heat exchangers, including: plate heat exchangers, shell and tube heat exchangers, finned tube heat exchangers, modular cooling tower systems, and refrigeration heat exchangers. The markets it serves include: energy, the oil and gas industry, the chemical industry, marine applications, food and beverages, and climate and environment. www.kelvion.com

Gavilon Grain, LLC – www.gavilon.com

Bennett Steel, Inc. – www.bennettsteel.com

DIG DIGITAL?