Asheville, North Carolina

How change happens

Business View Magazine interviews representatives of Asheville, North Carolina for our focus on Sustainability and Social Equity

In June 2020, North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality blitzed the State with its 372-page directive on climate change adaptation. Titled the Climate Risk Assessment and Resilience Plan, it served a crystal-clear message to all policy makers and government stakeholders that the time to act was now.

“The latest climate science underscores what we already know firsthand,” cautioned Governor Roy Cooper in his introductory speech to the report. “There will be increased temperatures, continued sea level rise, more precipitation, more intense hurricanes, more severe thunderstorms, and more storm surge flooding.” The good news was that the Plan supported the critical lens that we still controlled our own fate.

Flash forward to 2021 and the climate change movement is mainstreaming through its integration with a global health pandemic that has on the one hand, disproportionately impacted the most vulnerable, marginalized people in the country and on the other, illuminated the social inequalities that have been some of the root causes of climate upheaval to date. A growing consensus has emerged regarding the science of climate change in recent years – the issue has transformed from a fight for eco-friendly practices to one for the communities that environmental racism habitually leaves in the dark.

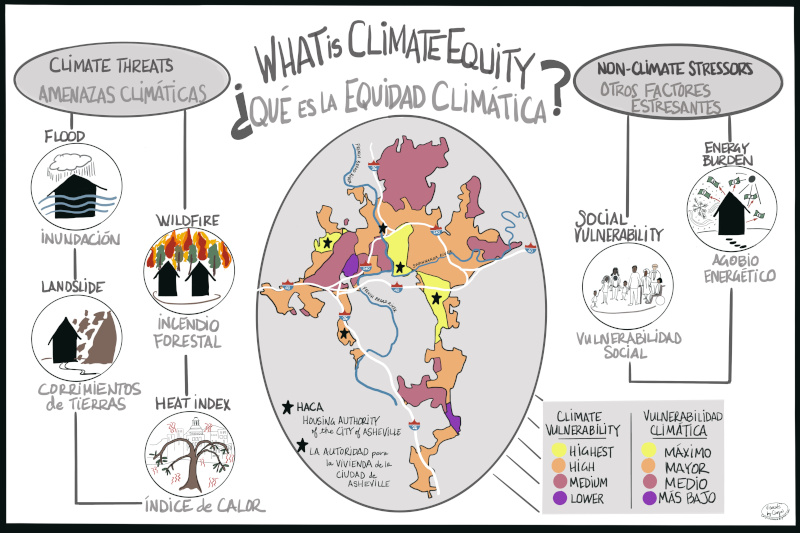

The City of Asheville, located in North Carolina’s scenic Blue Ridge Mountains – incidentally, one of the few areas left in the world yet to have experienced any significant warming – responded early and proactively to global and state-wide imperatives to grow a cleaner, more resilient, and inclusive economy by establishing what it calls the Climate Justice Initiative. The City of Asheville is working In partnership with Tepeyac Consulting, a national consulting firm that catalyzes strategic approaches to advancing social justice movements. The collaboration between Asheville’s city administration, community members, and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) leaders seeks to shape a locally relevant, inquiry-oriented, working definition of climate equity.

On January 28, 2020, Asheville became the first community in North Carolina to mandate a “Climate Emergency,” setting rigorous goals to counter warming greenhouse gases and their disparate impacts based on race, economic status, and area of residence. While Asheville waits for federal assistance to accomplish these steps, municipal staff members are zeroing in on connecting sustainability to racial justice work, using information compiled from “listening and learning” sessions that invite the historically underserved and marginalized to speak to those imbalances.

“When we started having those conversations about global warming and climate justice, part of that was really coming to understand ‘what did that mean?’,” shares Marisol Jiménez, CEO and Founder of Tepeyac Consulting. “What did that mean from the perspective of people who are living on the frontlines? For Black, Indigenous, and people of color? What was their definition of climate equity? What are the ways that we could learn from BIPOC communities about what it means to be resilient; to survive things like COVID, and to survive things like structural racism? What are the ways that they’ve built structures of support and what might those look like in a future of climate collapse?”

The depth of reflection and awareness that the listening + learning sessions highlighted underscores a readiness to dig in to the work. Now, civic imagination in Asheville is being mobilized as a skill and a tool, both for activism and for city governance.

“We’ve done one-on-one conversations with BIPOC frontline leaders all around Asheville,” Jiménez reports. “Through those, we’ve come to a deeper understanding of how critical it is to consider structural racism and the climate crisis as intertwined realities. People were clear that in order for us to be resilient and prepared in a climate crisis, there had to be a few things. One was land sovereignty. It’s BIPOC people having meaningful access to land ownership and land trust, for everything from shelter to water to food. Another was the resources, spaces, and support to create resiliency hubs – mutual aid systems that our communities have created as ways of making sure we’re taken care of. A third one was BIPOC green economy. Who’s retrofitting the buildings? Who’s creating and installing solar panels? Because that’s an entire economy.”

In subsequent phases of the project, Asheville’s Climate Justice Initiative hopes to get city government and frontline communities on parallel tracks to tackle the climate emergency. “Part of our attempt is to try to figure out ways where we, from a city government perspective, can learn from and lift up the work that’s already going on in our community,” offers Sustainability Coordinator, Kiera Bulan. “We’d like to continue to build these bridges so that our community members who are doing this good work are informing government processes.”

One thing that will shape policies and projects going forward is a screening tool informed by the Climate Justice Data Map, listening sessions and story circles with elders from Asheville’s historic communities of color. “It’ll be a tool that we can employ within our departments, to be able to really evaluate city plans and projects through the lens of the lived climate emergency,” Bulan explains.

The Office of Sustainability’s next steps in this climate justice work will be to turn its attention to grassroots actors as critical agents in the transition toward sustainability, mitigation, and crisis adaptation. “I think it was very easy for our Office to recognize the place of privilege that we sit in,” says Chief Sustainability Officer, Amber Weaver. “Even though I am also a person of color, I am still a government employee. I am still a person of privilege. And that wasn’t the demographic that we needed to hear from.”

Weaver shares that she sought Jiménez out in the hopes of bringing BIPOC voices to the center of the discourse on the climate crisis. “Those community members [BIPOC], their information is sacred,” Weaver affirms. “A lot of times, the government comes around, poking and prodding and asking questions. I wanted to partner with Marisol to really hear those voices and lift them up.”

“Things like story circles and speaking to our elders – this isn’t new community technology,” Jiménez explains. “But our approach and how we’re doing it is unique. Listening, learning, dialogue, engaging people at the frontlines, in leadership. And not just to be consulted. Not just to be asked, ‘What do you think?’ but to be following their lead. Which is really, I think, an important distinction. This isn’t about how do we help BIPOC communities. It’s about how BIPOC communities are holding some of the key answers to surviving climate crisis.”

But there’s a lot of work still to be done, just in terms of trust-building and trust repair, according to Bulan. She elaborates, “Climate justice is an issue that, when it breaks down to its specific elements like access to clean, healthy water and a safe place to live, everybody cares about. And yet, it disproportionately affects residents of our community differently depending on where they live, depending on race and ethnicity. And so, to be most helpful, we’ve got an opportunity where we can begin to create solutions based on what people already know through their lived experience. Which roads are flooded most often? Who’s at higher risk? What are the neighborhood supports in times of need, like the COVID emergency?”

“There’s always been a structural divide in our community,” Jiménez maintains. “And there’s incredible organizing that happens across our communities to try to figure out how we heal from that and build equity. But it’s a process, and the city’s only really just started.”

From the city government’s perspective, Bulan says, “Motivating connection and conversation about why climate is so important seems like low hanging fruit but is in fact part of a real effort toward transformational change that starts with authentic engagement.”

She admits, “It’s hard to name exactly what that looks like , but I think there’s a cultural shift that we’re trying to navigate through. Not just listening, not just asking for input, but really learning how we can be led by our community members on issues that are central to health, safety, and wellness.. Establishing shared definitions and language along with trust-building and follow through is foundational to better understanding how institutions and community leadership collaborate to generate relationship-based ideas to begin addressing critical climate issues alongside compounding factors of oppression.”

AT A GLANCE

Asheville, North Carolina

What: A diverse, community-oriented city of 95,000

Where: Blue Ridge Mountains region of western North Carolina

Website: www.ashevillenc.gov

PREFERRED VENDORS

Brooks Network Services – www.brooksnetworkservices.com

Brooks Network Services is a veteran owned business headquartered in Gibsonville, NC. We offer fully managed IT services (MSP), project-based deployments and security solutions. We are proven, with 30 years’ experience in Government, Manufacturing, Insurance and Healthcare. We are HiPAA certified and Cisco Premier Partners.